Most people would never think that computers could create compelling or interesting art or music – the human brain has intricacies and nuances that are difficult to replicate, especially when dealing with artistic expression. However, in this amazing technologically driven age, there are in fact computers, programs and algorithms that have been designed to create unique and fascinating musical compositions and the artistic visualizations that represent it, thanks to a specific group of innovators like R. Luke DuBois. Currently on view at the Beall Center for Art + Technology is the exhibition, “Music into Data::Data into Music,” an exhibit that focuses on a variety of ways in which DuBois uses video, computational processed sound and digital images as compositional elements in his artistic and sensory-based creations.

Photo by Will Lee Yang

The Beall Center for Art + Technology focuses on supporting and exploring research, programs and creations that deal with the complicated relationship between science, technology and art. With exhibitions that push the boundaries of what we think museums or gallery experiences should be, the Beall Center creates innovative projects that showcase how technology can be integrated within the arts to create new forms of interdisciplinary research and expressions to carry the act of creation forward into the future with attentive and interested audiences.

Walking into the Beall Center, a dark and calm energy surrounds you and light musical sound seems to float like vapor all around the space. Looking into the vast exhibition space, there are meditative moving videos, subtle noises that cling and clang together to create a windchime-like effect, and the spotlights throughout the space provide hints at what deserves your attention in this dark and curious space. The first piece to greet you as you enter is one of DuBois’ Synaesthetic Object works; it moves and floats and dances to a simplified musical composition. This particular work – although part of his larger series some of which has been shown previously – has never been shown before, and stems out of a project DuBois worked on creating VR therapy videos for people suffering from PTSD. His larger Synaesthetic Object series is a body of work that explores the visual relationship to something auditory, like an image of music or a musical composition of an image. Created with jazz music, this Synaesthetic Object shows us an intense digital image that moves and changes to a computerized and digitized jazz composition and never settles down.

As you turn the corner, a gorgeous and ominous table beckons you to come closer. Large and small patterns of circles are drawn all over this long sheet of paper that is reminiscent of a print-out by an EKG machine or a seismometer. Upon closer inspection, this is actually a record of songs and a year of DuBois’ life. This piece, “A Year in MP3s,” was a 365 day-long project where he composed and recorded a song a day, netting a total of 72 hours worth of music documenting his life and creative process for one year. From September 10th, 2009 through September 10th, 2010, DuBois created a piece of music every day and posted it to an RSS feed online. The project was inspired by a similar undertaking, called 365 Days /365 Plays by playwright Suzan-Lori Parks. “A Year in MP3s” documents a year of the artist’s life. Some are musical sketches for longer pieces, some are pop songs that the artist wrote while waiting in airports, and some are taken from live performances with collaborators and friends. The large physical record of his creations is complemented by a number of small MP3 players for people to peruse through his musical year at will.

Photo by Will Lee Yang

To the side of “A Year in MP3s” is a huge projection of a grid of images consisting of 12 smaller squares, all videos, each highlighting a musician playing their instrument, in black and white. “Vertical Music” (for 12 musicians filmed at high speed), is a video project that captures a live musical performance but slowed way down so that it may be viewed and experienced at one-tenth the original speed. The subtly nuanced and gestural composition is inspired by Kramer’s notion of virtual time, or the subjective passing of time felt by a listener (rather than absolute time). So, by viewing and listening to this focused performance, the project provokes an internal inquiry on the collapse of time that is inherent to any performance documentation and the notion of time itself, the senses and what aids our human experience in time.

With much of DuBois’ work, the history of the portrait is of great influence, as is the concept of identity and documentation and how art history has been shaped previously, and the exciting possibilities with new forms of expression, communication and documentation. DuBois’ screen-based video portraits of musicians and friends show us this interest intensified. In this exhibition there are seven video-based portraits of musicians in full color and slowed down to show us the details and nuances of each sitter, giving us more insight along with more visual and auditory information. The video shows us the sitters playing their instrument of choice, enhancing the experience by the auditory experience of the slowed track they are all playing.

Along these same themes are other works where he has created computerized algorithms that are constantly recycling visual and auditory information to create new and interesting creations. He has two pieces that touch on the art of political speeches and the similarities between all political speakers with regards to their persuasive and manipulative language.

These two pieces are also generative video works that have no end.

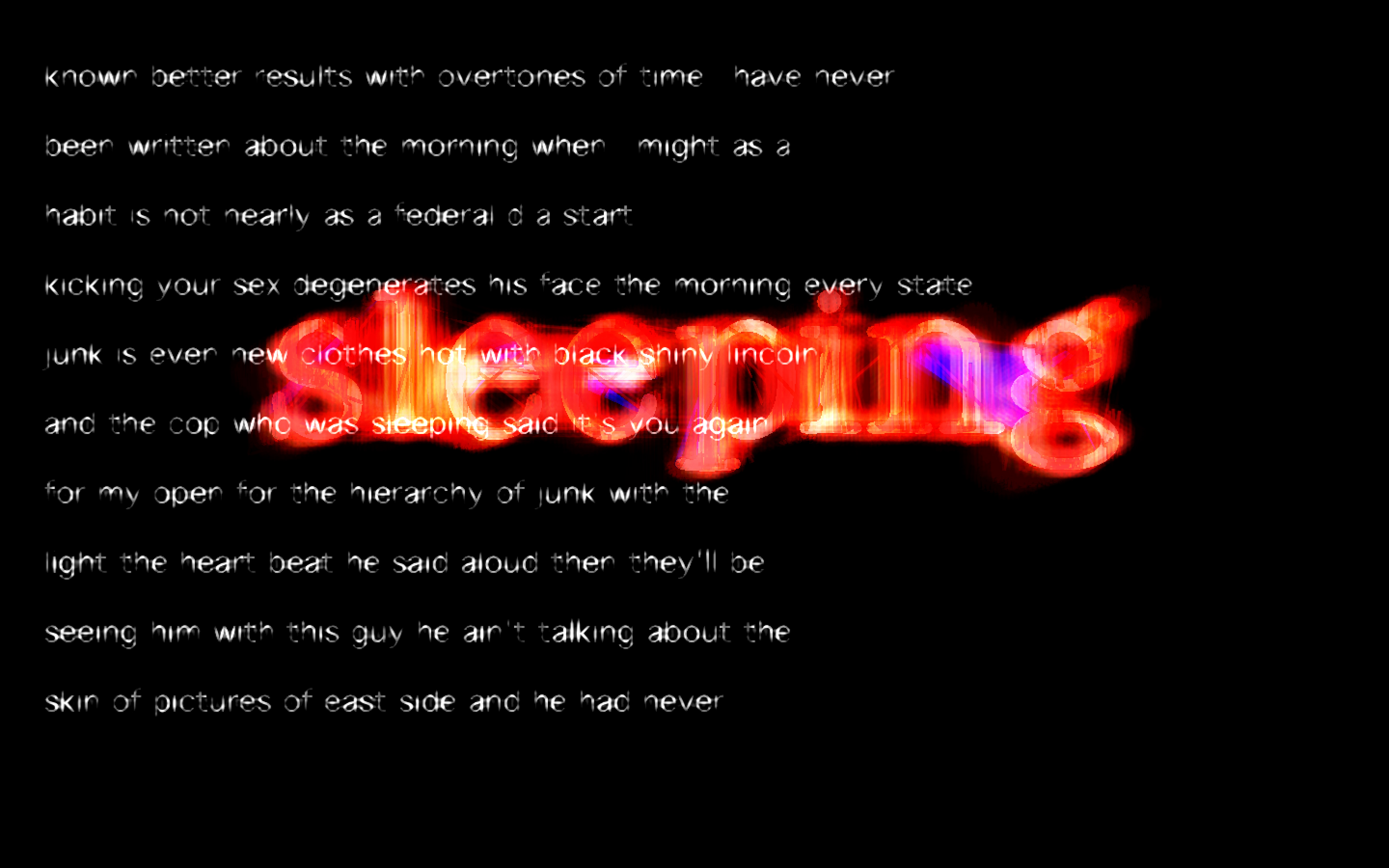

DuBois also highlights his technological and emotional interest with “Prosody: WSB,” which uses a cut-up technique to re-imagine William S. Burroughs’ poetry, constantly generating new and interesting poetry and the visuals to go along with it, behind a type writer that is similar to the one Burroughs used. Using a hidden Markov model and an unreleased audio recording of Burroughs reading “Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict,” the artist created a software engine that rearranges Burroughs’ text with particular care taken to preserve his extraordinary vocal tone and his singular vocabulary.

Throughout this exhibition, DuBois finds avenues and pathways for his audience to discover and become aware of our own humanity and our creative desires; he does this by playing with the two worlds we don’t often see interacting – art and science – and he uses art and science to create fascinating and innovative artworks through language, music and imagery.

Beall Center for Art + Technology will be closed December 17, 2018 – January 7, 2019.

“Music into Data::Data into Music” will be on display through February 2, 2019.

712 Arts Plaza, Irvine

(949) 824-6206

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting Irvine Weekly and our advertisers.