The Beall Center’s Ian Ingram exhibition explores what the eponymous artist refers to as “animal morphology, robotic avatars, interspecies communication and technology in natural environments.” The 21 pieces in the exhibition involve 14 robots — all appropriating animal forms and behavior — that Ingram built and filmed over 20 years in the high, desolate landscapes of arctic fells, in city streets, parks and ponds, and in back-country lakes and mountains.

Ingram, who created several pieces in this show during his recent residency at the Beall Center, has a Bachelor’s degree in Ocean Engineering and a Master’s in Ocean Acoustics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, plus an M.F.A. in Visual Art from Carnegie Mellon University. He has exhibited his work nationally and in Halifax, Copenhagen and Amsterdam, among several other foreign cities.

Much of his work focuses on “synanthropic animals,” or on those “most closely tied to ourselves and our places.” He explains that the robots function similarly to the animals they communicate with when the subject of their focus (whether raven, lizard or worm) appears on the scene. He adds that the robots have detailed flashbulb memories of the times when the subjects of their intent (the real animals) are perceived to be nearby.

Indeed, the animal universe that Ingram replicates robotically and in films is fraught with challenges and danger, along with delights including liaisons with flowers and mating. Beyond the scientific and artistic aspects of his robotic experiments, Ingram is engaging in a deeper understanding of the animal world. If all of this sounds fantastical and futuristic — and a little hard to wrap your mind around — you’re not alone. Irvine Weekly asked the artist to introduce us to his ecosystem of avatars, creature by creature.

View of main space. Large projections of “Whisking Flowers” (2019-2021) and Lizardoz (2014) are prominent, with “Rats with Wings” (2019-2020) in the foreground. (Photo credit: Yubo Dong with OF Studio)

IRVINE WEEKLY: When did you first begin creating robots?

IAN INGRAM: I made my first real robot when I was 10. It gathered chalk from our schoolroom’s chalkboard tray, and then signaled success when it reached the end of the tray by doing a kind of dance. In 1995, I started to build a robot that would inhabit and somehow belong in the tiny habitat formed by islands off the New Hampshire coast. I am still working toward finishing that project.

Please describe Lizardless Legs.

It is one of a series of robots that attempts to enter the border disputes of Western fence lizards by watching for the lizards’ territorial push-up signals and responding with its own push-ups. The push-up gesture dominates (as it is the robot’s main function) and is also a mating display. So to a degree, Lizardless Legs is a lizard sexbot (or a robot designed for sex).

And Nevermore-A-Matic?

This piece tries to tell our stories about the end of the world to ravens using coded beak wipes. The birds likely don’t really understand, but from the biosemiotics (signs and codes) of excessive beak-wiping, they might gather that the robot is deeply worried about something.

Left: “Rat King” (2019-2021). Middle-right: “Cinderella” (2019-2021) and “Fine Feathered Friends” (2020-2021). Foreground: “Sleeping Beauty” (2019) (Photo credit: Yubo Dong with OF Studio)

Love this name – Danger, Squirrel Nutkin.

Prey animals alert each other to danger using alarm signals. Danger, Squirrel Nutkin – a robot looking for squirrel predators like dogs, foxes, cats, hawks and people – alerts the local squirrels using their own alarm signals, which is tail flagging. The robot has three tails, so its message could amount to a supernormal stimulus.

And Elongate Evans?

My residency at the Beall and collaboration with neuroscientist Steve Mahler there led me to a deliberate turning towards synanthropic animals. Steve keeps as pets a breed of rat called Long Evans. I spent time with them at night in the dark in his garage. I became interested in how synanthropic animals’ bodies fit into the built environment, and how they find facsimiles there of the places where they evolved. And because of the rat’s proclivity for chewing, I armored and enclosed my robot’s vitals in ways that I have rarely done.

Now tell us about Marvelous Meat.

Marvelous Meat is a short film, akin to a nature documentary of Nevermore-A-Matic in arctic Finland, where it broadcasts its message of doom into a supposedly pristine landscape full of crows, magpies, foxes, flies, and molting reindeer. It oversees a carcass made of pig, cow, sheep, and reindeer parts, bought shrink-wrapped in plastic at the supermarket.

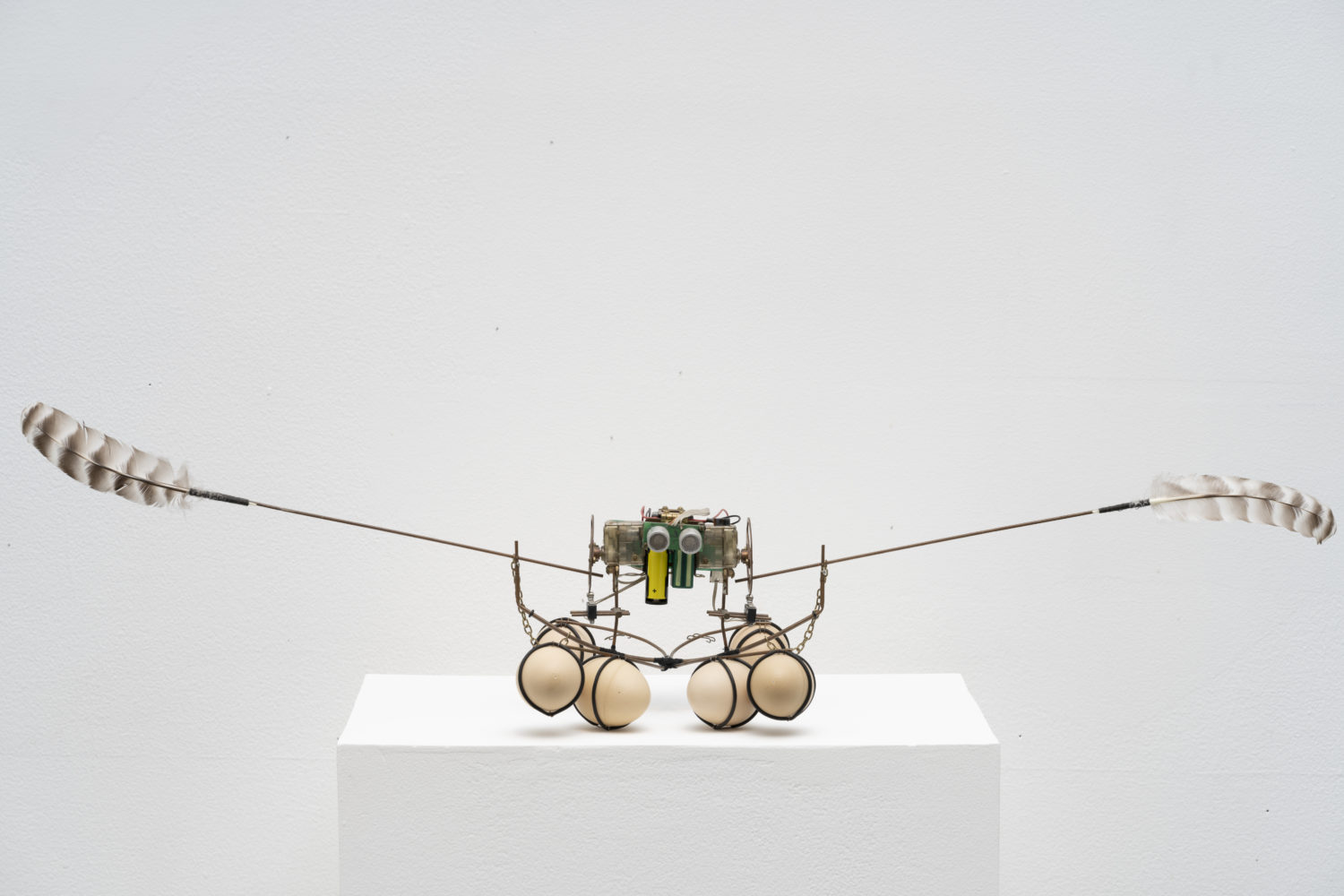

On Beyond Duckling (2004) (Photo credit: Yubo Dong with OF Studio)

Please describe the On Beyond series – On Beyond Duckling, On Beyond Pond, and On Beyond Mother Goose at the Lake.

In the early 2000s, I was trying to create artificial symbiosis. When I failed at that (symbioses are really million-year projects), I tried to create what I called sculptural symbiosis. This led to a series of robots engaging in their own mating rituals in wild places while cohabiting with the animals and plants there. On Beyond Duckling never had a mate, making its overtures plaintive and forlorn. To make up for that, I made On Beyond Mother Goose who did have a mate, On Beyond Father Gander. They executed their synchronized mating ritual of bows and spins aligned with the Earth’s magnetic fields while miles apart because they had a linked sense of time’s passage.

Rat Re-Embodied as a Robot (2019) (Photo credit: Yubo Dong with OF Studio)

Last but not least, tell us about your rat-related installations.

There are quite a few rat projects. Two are new bodies for rats: Rat King, the entanglement of these new rat bodies; and A Whiskerer, a rat re-embodied in a form that allows it to have gentle liaisons with flowers. They are built from surveillance cameras. With the piece, Dropping, the robot’s surveillance camera goes physically all the way down to the floor from the gallery ceiling because its focus is on that plane and on the scurrying and activities occurring there. Rats With Wings connects rats with their feathered counterparts, the pigeons and gulls. Sleeping Beauty gives surveillance cameras a chance to rest from their vigilant watch, dreaming during the day in REM sleep about the rats it saw during the night.

In working with Mahler and talking with his colleagues about efforts to understand how the brain encodes memories during flashbulb memory, I became interested in engaging with my robots’ memories. With a prey animal like a rat, life is a risky business with an associated need for vigilance and crystallizing lessons from traumatic and near-traumatic events. The surveillance cameras I use, beyond the similarities in color and form they have with rats, exist in a world of vigilance with the presumption that something bad is always about to happen.

“Ian Ingram” is on view through March 5. UC Irvine Beall Center for Art + Technology, 712 Arts Plaza, Irvine. 949-824-6206. Mon.-Sat., noon-6 pm. beallcenter.uci.edu

Tiny Tussle (2014) and Ziggy Dirtdust (2020) (Photo credit: Yubo Dong with OF Studio)

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting Irvine Weekly and our advertisers.