For those looking to connect more with the artistic and cultural roots of Southern California, the Laguna Art Museum has welcomed a new exhibit you shouldn’t miss. From now until May 27, the museum is hosting an exhibit of select works from the famed Self-Help Graphics & Art printmaking shop and studio. If you haven’t heard of them before, they’ve been a pivotal artistic institution for some time. They were founded in 1972, and as they developed their programs and facilitated wider ranges of artists, they became a main contributor to emerging Chicano and Latino artists and cultural movements.

If you want to fully appreciate the works being displayed, it helps to understand the history that made them possible and necessary. In 1970, as the Chicano Civil Rights movement was peaking, two young Mexican artists named Carlos Bueno and Antonio Ibañez, joined by Frank Hernandez and various other Chicano artists, met Sister Karen Boccalero. She was a Franciscan nun and Temple University-trained Master Artist who would eventually assist in the rise of Self-Help Graphics. At the time, they were getting increasingly frustrated with the lack of facilities accessible to young Chicano artists. Furthermore, some in the art community had yet to accept the legitimacy of the Chicano art movement as a unique cultural expression. With all of this in mind, they set out to develop a solution.

After earning a grant from the Order of the Sisters of St. Francis, they acquired a building in East L.A. that had once been a gymnasium. By 1972, Self-Help Graphics & Art officially opened its doors to overwhelming community support. They soon outgrew their facility, and in 1973, they took a grant from the Campaign for Human Development to purchase 7,000 square feet adjacent to their existing space.

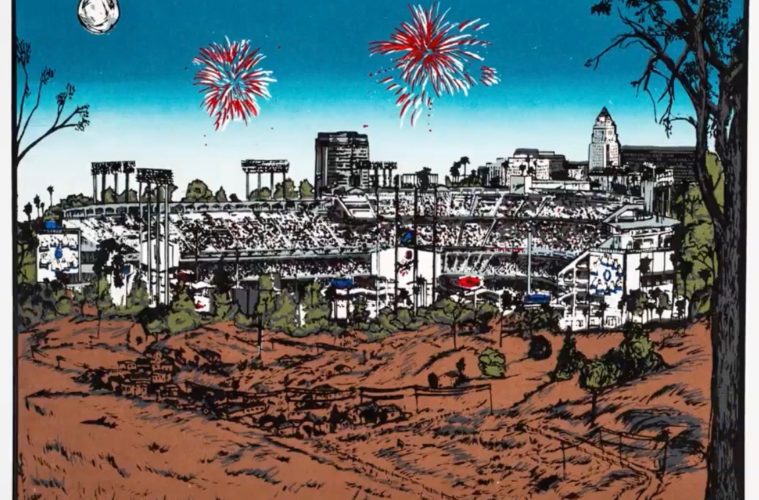

- Miyo Stevens-Gandada’ “Chavez Ravine” – 2016

From the beginning, one of the main goals of Self-Help Graphics & Art, SHG for short, was promoting appreciation for Chicano heritage; the Chicano Movement taking place at the time inspired this focus. Rather than tout their European Spanish heritage, Chicano activists emphasized their pre-colonial past, arguing that Anglo socio-cultural values were impacting their indigenous culture. SHG and these activists feared that Chicano youth might forget their roots or grow to disdain their culture in the midst of Anglo societal norms.

SHG, along with wanting to expose barrio children to various types of art, felt their main goal should be, according to their website, to “utilize art forms to instill within these children a positive sense of self, community and culture.” Many of these barrio children were migrants or the children of migrants, and didn’t have a strong grasp of spoken or written language. Art doesn’t require a command of language, and was therefore viewed as the key to achieving their goals. There was one significant issue in the way: location. The physical geography of East Los Angeles isolated a lot of the target group, preventing them from easily accessing the services offered at SHG’s facilities. Since many in the community couldn’t get to SHG, they had to find a way to go directly to the community.

In August 1975, the solution came after an intense round of fundraising, taking the form of the Barrio Mobile Art Studio. With this customized van, they were able to introduce children in these communities to filmmaking, silkscreen, photography, sculpture, painting, puppetry and the batik dyeing technique. Thanks to a contract with the Los Angeles Unified School District, they also brought their program to various East L.A. elementary schools and gave them the sort of multicultural arts education that their curriculum didn’t provide. Even as it was eventually phased out in 1985, it served as a prototype for future multicultural curricular programs that LAUSD would adopt later.

The works that have emerged from SHG since their inception serve as a genuine reflection of Chicano and Latin history and culture. Various artists that worked in their studios detail those connections in the documentary “Entre Tinta y Lucha: 45 years of Self-Help Graphics & Art,” which is featured in the Laguna Art Museum exhibit.

One person featured, Chaz Bojorquez, guides viewers through his 1994 piece, “Por Dios y Oro,” a print of a sculpture that details how his people’s culture has been impacted by colonialism. He describes the significance of a cross that he placed graffiti-style in the middle of the piece, discussing how “the Conquistadors came, just like a gang, [going through] the neighborhoods and tagging their names.” He then points to some scrawled initials in the corner, “S/P, Spain & Portugal,” along with a list of all the other countries, “like gangs, who came and started colonizing the Americas. This is a documentation, this is an announcement, a declaration of the conquest.”

Another artist, a woman named Miyo Stevens-Gandara, immortalizes a sign of a more modern issue with “Chavez Ravine,” a 2016 print depicting the origins of Dodger Stadium. The stadium, for those unaware, was built on the site of a Mexican-American community called Chavez Ravine. It had initially come under attack in 1949, when the L.A. City Housing Authority marked it as a prime redevelopment location. Some years later the mayor, Norris Poulson, purchased the land at a fraction of its price, persuaded the Dodgers owner to move the team to L.A., and forced out those who didn’t sell their property via burning and demolition. As Miyo describes it, this was an early example of people in the modern era “being moved off a site [for a building project] against their will. It’s like gentrification. [The piece] is supposed to serve as a reminder of what’s happening now. It’s happening in Boyle Heights and it’s happening all over Los Angeles.”

If you’d like to further acquaint yourself with this artistic and cultural movement, the Self-Help Graphics exhibit at Laguna Art Museum will feature select works from their studio dating from 1983-1991. Find out more information on their website, and be sure to check the Irvine Weekly for more updates on the Orange County art world.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting Irvine Weekly and our advertisers.