Continuing on the curious exploration of the art world introductions of the graduating University of California, Irvine MFA students, additional relevant themes and ideas seem to reverberate in the work of young artists and in our collective consciousness. In this second round of solo exhibitions for MFA candidates Andrea Welton, Mountain House, Nicolas G. Miller, Ariel McCleese and Michael Thurin, the works on whole are more ephemeral and touch on more abstract yet interesting ideas that feel relative to what’s going on in the world, much like the first round of MFA shows did. Of course, viewers are left to ponder many of these works and their meanings, like a puzzle we are forced to solve without proper tools, making us call into question the success of the artworks and the overall ideas explored.

(Courtesy of Evan Senn)

One successful artist in the mix drew crowds of silent admirers slowly walking around and staring at her creations for as long as time would allow. Andrea Welton’s large-scale painted musings of our natural Earth hypnotize viewers with little effort. Seven large paintings take up the front space of the University Art Gallery, and each has a fascinating visual dichotomy going on inside of them. They are simultaneously stoic and ever-moving. Each one is a gorgeous natural-looking stain or slice of the Earth with remnants of actual crystal and rock lining the crevasses in the compositions. Some of the compositions recall slices of mountains with years of growth and change locked away inside themselves, only to be revealed in these cuts; some recall petri dishes looking intently at the cellular makeup of a strange and beautiful organism. They are both quietly whispering painful confessions and shouting loud shrieks of love and poetry.

Welton approaches her work as an investigation into our personal relationship with the landscape, some with love and adoration, others with scientific curiosity. She seems to find a way—through her work—to also pose an internal inquiry about the artist’s role in creation in comparison to science and time. Her work gives viewers an inside look at the landscape of our planet and the landscape of the artist as well.

In the back-gallery space of the UAG, Mountain House showcases an installation/performance, Two Weeks in May, that invites viewers to ponder and question ideas about nature, but also forces viewers to consider our responsibility to the planet and the land that we are stewards for. Taking its title from Suzanne Lacy’s Three Weeks in May from 1977 which confronted the rape and abuse problem for women in Los Angeles using art and non-art activities over a three-week period, Mountain House evokes a kind of parallel to the rape of our planet and of indigenous cultures. A visually puzzling collection of items, specimens, barely built structures and nooks resembling an exploratory team’s dwellings in some far-flung land, Mountain House makes the viewers feel as though they are a part of the exploratory team, discovering something new—what it is that they are discovering, however, is left unknown.

Learning more about the collective of Mountain House, it seems as though they are interested in educating the public about the natural environment and indigenous cultures through art-making, performance and education. Their work, however, is difficult to access for regular gallery-goers, having small events throughout the two weeks the show is up for, creating collaborative opportunities with the UCI community through performance, skill-sharing and knowledge-building with very little art objects to be appreciated without previous education, planning or insight.

(Courtesy of Evan Senn)

The success of an artwork is often considered in the experience of the viewers, which the artist must consider in creating and presenting the work; who is the audience and how will they relate to this work? Paintings and drawings have an easier time than many other types of art to communicate their messaging and themes to their audience, due to the longstanding common understanding of their forms of communication. Contemporary installation, video and performance art have more difficult experiences relating their audiences. Without audience art education or very straightforward visual language used by the artist, many viewers will not connect to performance art or video art as successfully as other two-dimensional art forms. This is the case with the MFA solo shows of Ariel McCleese, Mountain House and Michael Thurin.

Michael Thurin’s pink-lighted performance piece, Chiffon and Indiscrete Glitter, at the Room Gallery is a performance and installation that utilizes large wooden slabs to mimic a modern dance stage upon which a large group of people perform a collaborative and abstract routine. The group of people performing go in and out of supporting one another physically in this routine and renegotiate the movable wooden stage floors over and over again together. They are in a sense building and breaking relationships in the process, but the viewers’ attention is split in so many different directions, the nuanced collaboration and codependency on view can easily be missed.

Daughters of Wolbachia (Courtesy of Ariel McCleese)

Although Ariel McCleese’s visually stunning short film, Daughters of Wolbachia, showing in the CAC Gallery’s back room, is a fascinating and hypnotic video work, the larger idea for this video work was difficult to find through the confusing story and creative language used. Touted as an experimental short film born of a feminist bacterial apocalypse, the story mimics the real-life bacterial domination of Wolbachia bacterium in arthropods, which utilizing feminization and male killing to colonize and destroy insect populations. This film shows us only a very short and intimate perspective of this parallel human female apocalypse through the training of two females by another female. There is a hard-to-navigate education happening, and an eventual shift of behavior as the female rise up and revolt against their teachings, but it is very difficult to understand without the prior knowledge of the insect bacterium story and would benefit from additional context. The visual language that McCleese uses, however, is absolutely breathtaking and she clearly has a gift for film aesthetics and direction.

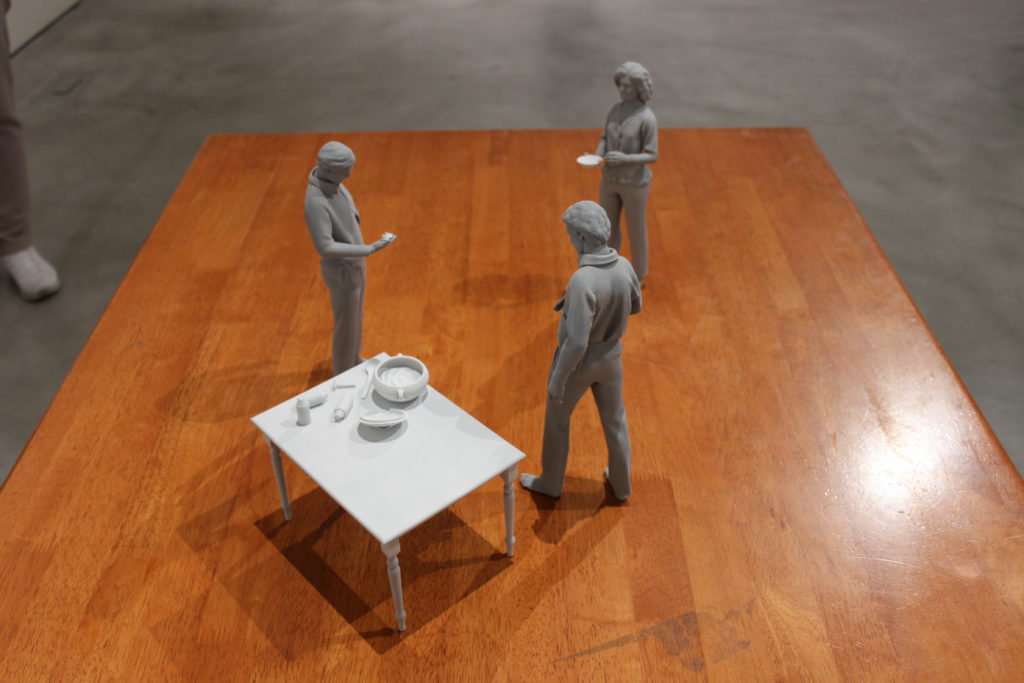

In the front space of the CAC Gallery, Nicholas G. Miller presents a curious collection of avant-garde miniature people and settings complemented by photographs of miniature settings with poetry, and an assortment of brightly colored clothes delicately hung high up in the space. This project, Spring / Summer, explores an experience in a world without weather and the puzzling decisions that one must make because of the lack of weather. With one nook of miniatures on a wooden table showcasing tiny adults dealing with everyday activities, and another nook highlighting a miniature young boy and a video camera on top of a filing cabinet, viewers are intrigued but confused about their relationship to one another and their own place as a spectator in all of this. This collection of visual assortments reads a bit like a coming-of-age story, with the clothes hanging in the center of the space, dividing these two strange phases of life with poetic musings and quiet moments as the focal points. Although perplexing, it is a fascinating presentation of silence, self and scale.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting Irvine Weekly and our advertisers.