In the ongoing, intensifying quest for true social equity, curator Bridget R. Cooks’ exhibition The Black Index makes the case for examining the volatile intersection of not only who is represented in visual culture but by whom they are depicted. In other words, as this remarkable exhibition posits, it is not enough that images of Black people are produced by artists and creatives – it specifically matters that it be Black artists who make them. Cooks, a UC Irvine associate professor of African American studies and art history, organized and curated the exhibition, which debuts at UCI before traveling to Palo Alto Art Center in May; the University of Texas at Austin in the Fall; and Hunter College in January 2022.

Dennis Delgado, Black Panther (The Black Index, UC Irvine)

The artists featured in The Black Index – Dennis Delgado, Alicia Henry, Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle, Titus Kaphar, Whitfield Lovell and Lava Thomas – take the power of self-representation to heart as not only an act of reclaiming the sovereign voice from the violent and insidious legacy of colonialism, but as a more perfect path to truth and complexity in art, and from there, in society as a whole. Across drawing, performance, mixed media, sculpture, and digital media, these artists take issue with the imposed mechanisms of “classification” endemic to the dominant American understanding of race, offering a poignant and self-determined set of alternatives.

Because of everything, the exhibition is only online (for now) but a well-produced virtual tour and other performance and conversation resources and even a curated playlist enrich the presentation. As you enter the site, perhaps the best place to start is with Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle’s Breathing Meditation, an unguided slideshow of drawings from her The Evanesced, The Untouchables 2020 series, whose gentle fades are timed to create serene breathing and a quiet state of open-mindedness and non-expectation with which to enter the exhibition. Hinkle’s large and growing suite of drawings represents the historical and present-day unsolved disappearances of Black women in loosely abstract, ethereal yet visceral “un-portraits” anchored in powerful details that somehow embody both erasure and endurance.

Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle, from The Evanesced (The Black Index, UC Irvine)

Dennis Delgado interrogates the racism built into policing and surveillance – and social media – technology, especially as run through facial recognition. Though we often think of tech as dispassionate, the reality is that the encoded structures and implicit biases of the largely white, male programming and algorithm workforce have follow-on effects in our society that can cause very real damage in application. Delgado uses the faces of icons of Black cinema as engaging touchstones for unpacking these dangerous dynamics.

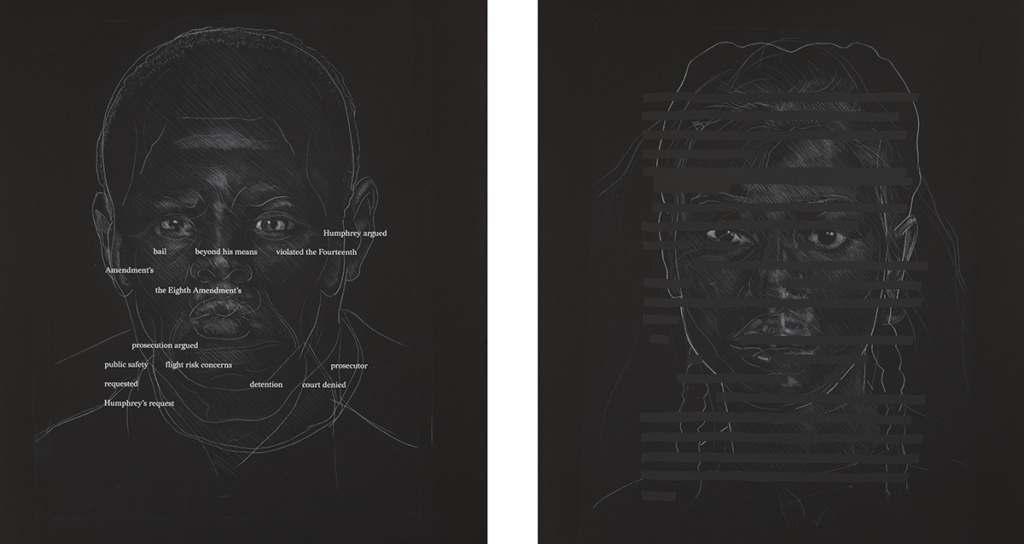

Similarly, Titus Kaphar worked in collaboration with Reginald Dwayne Betts, a civil rights lawyer to examine the oppressive, destructive and probably unconstitutional effects of the cash bail system, which like so many other public institutions and policies, disproportionately impacts Black communities. The Redaction features poetry by Betts by sampling and excising texts from Civil Rights Corps lawsuits, overlaid on Kaphar’s etched portraits of incarcerated individuals. The works are quiet and pensive but also jarring as they express the absurdity of this pernicious inequality in a hybrid language that reveals the individual humanity behind the statistics and court battles.

Titus Kaphar, “Redaction (San Francisco),” 2020. Etching and silkscreen on paper. Courtesy of Titus Kaphar and Reginald Dwayne Betts (Photo by Christopher Gardener)

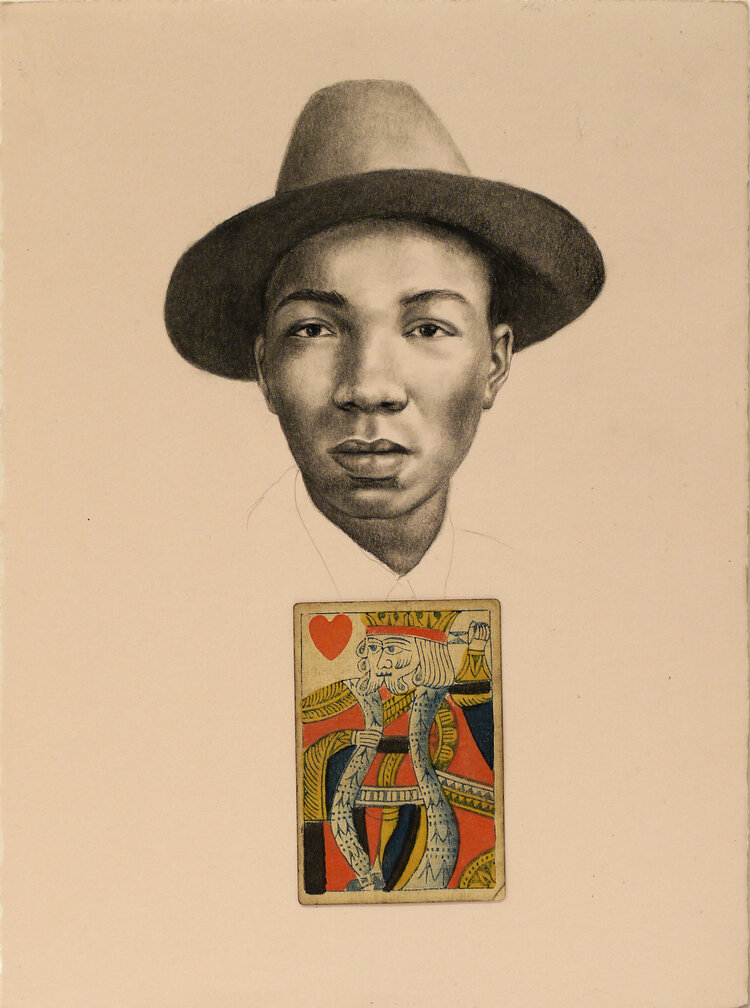

Whitfield Lovell combines drawn portraits of remembered figures from the African Diaspora – specifically people who lived in the time after the Emancipation Proclamation and before the Civil Rights Movement – with suites of ordinary playing cards. In these works, the cards symbolize the role of “chance” or indeed the power of larger forces beyond our control to shape our lives, while at the same time creating intimate works that evoke the energy of playfulness, social gathering, forecasting and inheritance. Cards are held in the hand, the energy of their users leave traces behind, and in this way something of the stories of bygone lives remains and gives even more life to the enchanting portraits they accompany.

Whitfield Lovell, Card XI from The Card Pieces (The Black Index, UC Irvine)

Alicia Henry too is interested in the energy transferred through materials – from the recycled leather she works by her own hand or buries in the ground to soak up all that earth magic, before transforming these skins into families of “witnesses.” Her suite of sculptural masks suggests the waiting cohort of ancestors and the gathering of collective testimony as to the unsettled past and the urgent present.

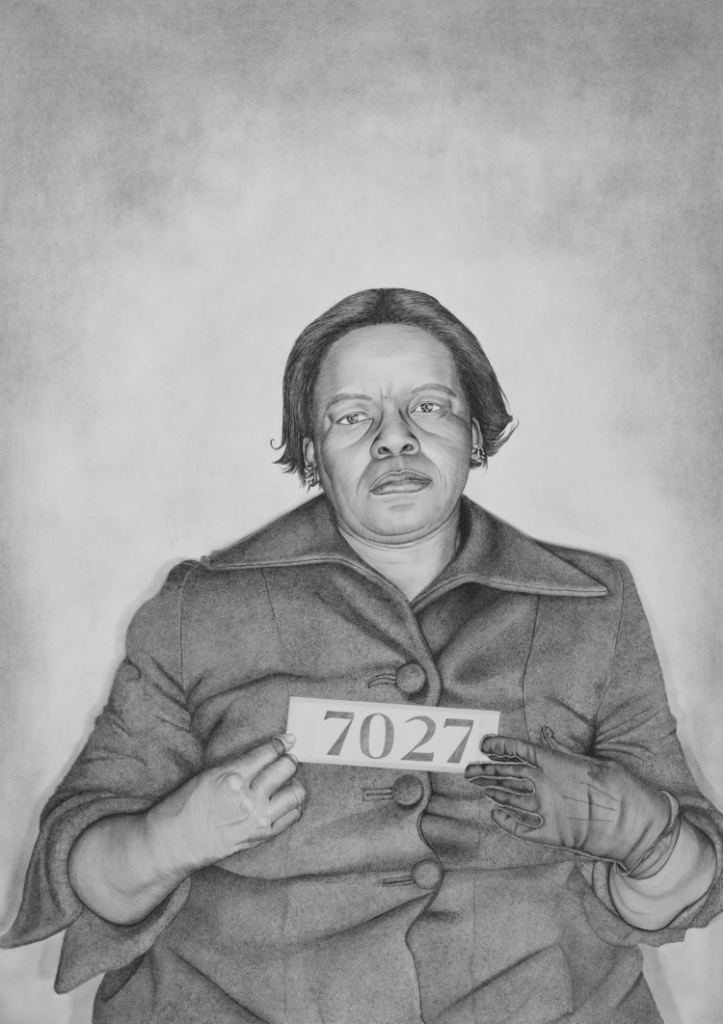

And finally, Lava Thomas’ Mugshot Portraits: Women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, transforms these records of arrest, intended by contemporaneous authorities to shame and frighten, into proud, emotionally rich depictions of these pioneering activists on par with the regal kind of imagery of a fully realized studio portrait. By showing the self-possession and inner strength of these early heroes not as dangerous criminals but as the valiant protectors of their communities, this series blends the past and the present into a march of quiet strength with which to face the future. The specific way in which this series in particular exists within the current political and social climate – not least in their centering of Black women on the vanguard of change – is the perfect capstone for this affecting and timely exhibition.

Lava Thomas, Mugshot Portraits: Alberta J James (The Black Index, UC Irvine)

Online at UC Irvine Contemporary Arts Center through March 20, along with online programming including streaming conversations and soon-to-be-released filmed music, dance and performance art. For more information, visit The Black Index.

The Black Index, installation view, CAC Gallery_UC Irvine © 2021 (Photo by Paul Salveson)

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting Irvine Weekly and our advertisers.