The first thing that hits you watching Todd Haynes’ new Velvet Underground movie (currently showing in local theaters and on Apple TV+), is the obviously non-traditional approach he’s taken in telling the legendary New York-based band’s story.

From the gorgeous gloom of V.U.’s debut with Andy Warhol and Nico to the dissonant pop-art audaciousness of their follow-up White Light/White Heat, the story is one of inspiration and evolution, but also collaboration, sometimes with contentious consequences, as the relationships between Lou Reed, John Cale and Andy Warhol all illustrate. It made for exceptional music and Haynes film captures all of the artistic alchemy.

The filmmaker, best known for the shimmering glam fantasy Velvet Goldmine (1989) and the surrealist Bob Dylan study I’m Not There (2007), speaks with Irvine Weekly via Zoom about the challenges of putting together his first music documentary, reflecting on the band’s influence and sharing how his love of David Bowie, glam rock and punk rock music inspired and infused his latest.

IRVINE WEEKLY: The doc is such a gift for Velvet Underground fans. And what is striking about it right away is how you used an experimental kind of structure that really reflected the band in their prime. As this was your first documentary, were there challenges in conveying the artiness of the group and reflecting the way they expressed themselves, and balancing that with telling the story in a linear way?

TODD HAYNES: Absolutely, that was really what the project was and what the challenge was. I learned so much about documentary. What you hear about documentary is that it’s all about a process, it’s a circular process where you keep going back into the well. And you’re writing it as you’re editing it and you keep learning about what the story is from what you’ve gathered in the well, and what you’ve gathered in your interviews. Of course this is a story that exists in the past and what has been written about that is finite. Members have passed away, so that’s closed. But you’re still learning the way to tell the story and for me that was always going to be the challenge. I really wanted that visual language, that ‘experimental’ language as you say, to sort of drive your experience, and the way you were maybe able to put yourself back into that time.

And you set up the experience wonderfully right from the very beginning with that initial footage. Putting their faces in close up and letting their eyes express who they are, backdropped with audio of their thoughts or other’s thoughts. A lot of the footage I’d never seen before, but some of the black and white footage looked familiar. From Warhol right?

A lot of the close ups of eyes, I think all that stuff is Warhol. Definitely the screen tests, the prolonged shots of Lou Reed and John Cale, and the band members, Niko and Jonas Mekas. As you know, he did hundreds of screen tests, when people would come to The Factory. Andy would ask you to sit down for an entire reel of film which would be about two and a half minutes long. You would just be asked to sit there, and just exist on camera. He did it with Bob Dylan and you see that little clip of Dylan in the corner, that’s his screen test. He did numerous screen tests of the Velvet Underground members throughout the years.

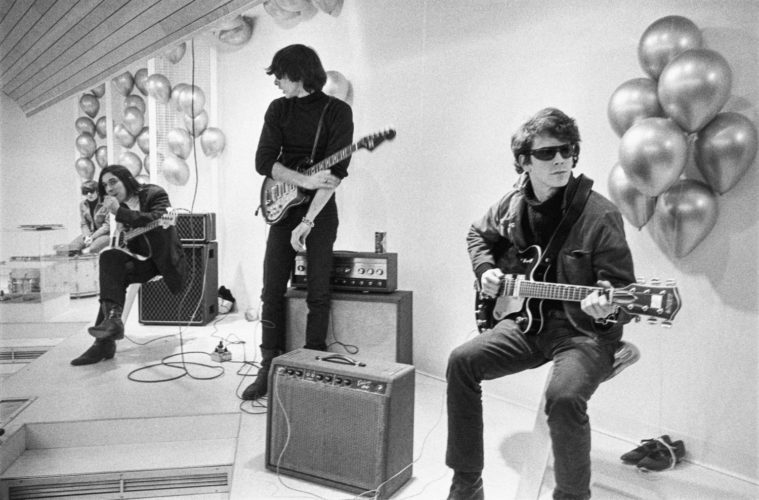

Todd Haynes’ The Velvet Underground (Courtesy Apple TV+)

I’d always seen, you know, stills from these beautiful screen tests, and sometimes clips in documentaries. I’d never watched an entire one in its entirety from beginning of the reel to end of the reel, where the white starts to shutter and you see the sprocket marks coming up. To live through one, and to really watch John Cale just existing on camera… Lou Reed who is no longer with us, sort of sitting there observing this documentary that’s being made about him. you know, you sort of feel like, ‘he’s watching me,’ or he’s watching ‘all of us’ hear his story. It sort of pulls you out, but it also sucks you back into the story very intimately.

It really does. I’d also love to talk a little bit about how you addressed queer culture and its influence on the band in the early days, in terms of going to clubs and things like that. Was that something that you consciously made sure to include?

Very much so. It was something that I knew was a part of this scene. I knew that was a part of Lou Reed’s, you know, experience as a young person. I didn’t know to what degree that was true, really, until I started to research it more closely and then hear from friends who knew him at the time. I think in a general sense, even when you weren’t necessarily gay yourself that sensibility, that attitude, permeated The Factory and permeated the New York culture in a way that they all responded to. It formed all of their sense of how they were outsiders. They were even outsiders to the rest of counterculture, which is what you see when they go to the West Coast, and clash with the hippies. You couldn’t have it more perfectly framed as a kind of New York state of mind and in my mind, a very queer state of mind, in how that clash occurs.

Absolutely. And of course I have to ask because it’s one of my favorite movies– I’m sure I’m not alone, asking a Velvet Goldmine question here. I don’t know if I’m reaching but when I was watching the documentary I felt like the relationship between Lou and Andy might have some shades of the Iggy/Bowie-inspired characters from Goldmine. You know, these two intensely talented, enigmatic artists and the kind of dynamic they have – not necessarily a love relationship, but a complex relationship. Doing a fictional film about two creative geniuses and their dynamic, and now doing a documentary that kind of spotlights this other creative partnership, which clearly had some tempestuous moments. Did you see parallels there?

We’ll sure. I mean, look there was intense curiosity, attraction, defensive anxiety that I think would define the relationship between Lou Reed and Andy Warhol. I think there was incredible amorous energy in the elemental relationship between John Cale and Lou Reed too. When you expose yourself to somebody in all those foundational ways as an artist and your ideas about what art is and how you want your music to sound different from everybody else’s music. It is like having a love affair, it is like exchanging something of intense intimacy, obviously. And the ways that that relationship would then have conflicts and fights and ruptures and then would sort of try to come back together years later, then have the same fights and ruptures again, that sort of looks like an early romantic relationship to me. You know it has all of the intensity of it. Maybe it’s even more intense than a real romantic relationship.

Then Lou Reed would have the kind of infatuation with David Bowie, which is what I sort of put into a fictional form in Velvet Goldmine with Brian Slade and Kurt Wilde in that film, which is almost more about Lou and Bowie, than it is about Iggy and Bowie, when you really think about the way that they interacted as creative beings and had kind of a bit of a romance. Whether that was literal or just creative I don’t know.

Velvet Goldmine (Courtesy Miramax)

Well, that film influenced a lot of people and it will always be remembered for its stunning visuals, as will this Velvet doc. I read that as a young person you were really inspired by David Bowie and his aesthetic. I guess everything connects.

Oh completely. I mean can’t you tell from Velvet Goldmine? It’s so funny like I was listening to Bowie and Roxy, and all that amazing glam and punk rock. I was heavy into that before I first heard the Velvet Underground. And what you realize is the Velvet Underground is the root to the stuff that wouldn’t have been possible – like glitter rock, like punk rock.

It opened up sort of darker themes and ideas and experiences and questions about sexual identity. Look, Mick Jagger was experimenting with what a man looks like and acts like and the androgyny that we’ve seen in rock and roll from as far back as Elvis Presley and even before that with Frank Sinatra. It’s been a sort of through line and rock and popular music, that androgyny, which took it a very extreme voice in David Bowie, obviously. But the Velvet Underground we’re talking about darker themes of experience, that I think opened up all kinds of categories of music that wouldn’t have been possible without them.

Indeed. Fans, of course, are going to appreciate the film but I also think it’s a nice kind of history lesson for a lot of people who don’t know much about the band as well. It reflects the actual energy of the time as well. And this was your first documentary ever. That’s surprising. You’re obviously such a music fan. Do you think you’ll do more now that you’ve done it? Do you prefer one genre over another right now?

Oh they’re so different. But you know this one, because of the avant garde films that are so specific to this moment and this band – that meant I could tell this story in the ways that you’re describing, using visuals and using something really palpable and visceral. Not just words or talking heads but something absolutely totally visual to make you see the music that was being described. That created a condition and a series of elements that were so rare and unique to the story in this doc. That’s really what made it special. I don’t think that’ll exist in other cases, but who knows.

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting Irvine Weekly and our advertisers.