Artist Tony DeLap, a founding member of UC Irvine’s Art Department, where he taught from 1965 to 1991, died May 29, 2019.

DeLap’s final public appearance, in January, was participating in a panel discussion at UCI’s Claire Trevor Theater. For this occasion, the lucid nonagenarian exhibited his characteristic dry sense of humor while discussing memorable events from his years at UCI.

Among his reminiscences, DeLap recalled walking onto campus one morning and observing several alien creatures that appeared to have come from a faraway planet. He admitted that he was witnessing the filming of the 1968 film, Planet of the Apes, about a crew of astronauts that crash-lands on a planet some time in the future. UCI’s ultra modern architecture by William Pereira apparently provided the perfect backdrop for that sci-fi movie.

Following is an edited/re-written version of a profile on DeLap that I wrote in 2018.

Widely considered one of Orange County’s foremost living artists, DeLap has produced a body of work that stands apart from the styles commonly embraced in the Southland. He builds “hyperbolic paraboloids” — shaped canvases that are hybrids of painting and sculpture that appear to change shape as the viewer moves around them. Their titles, including “The Honest Ace” and “Queen Zozer,” pay homage to the artist’s lifelong hobby and love of magic.

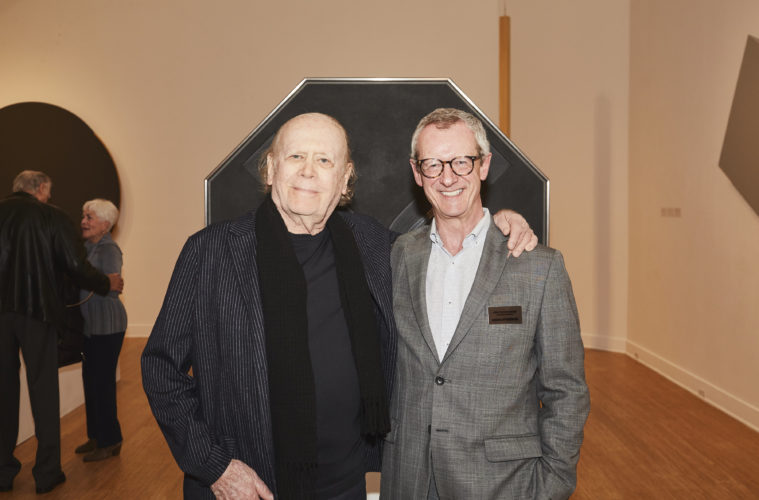

(Courtesy of Laguna Art Museum)

In 2018, visitors to the Laguna Art Museum had the opportunity to view 80 of DeLap’s works from collections around the country in the exhibition, “Tony DeLap: A Retrospective.” Covering the artist’s career from the early 1960s to the present, the exhibition was curated by L.A.-based critic and poet Peter Frank, who has been writing about DeLap’s work since the 1970s. As Frank explained in the accompanying catalog, DeLap “wants to make art that awakens its beholders to the eloquence of form and to the circumstantial nature of perception … that is well crafted, whether by hand or by machine, whether out of artmaking materials that go back millennia or out of the latest synthetic substances and processes — ideally, all in combination … that stays universal by staying personal, that honors aesthetic ideologies by merging them, and that shrugs off the art market’s tendentious demands by simply sticking to its guns.”

DeLap, a serene and focused older gentleman, discussed in an interview his several-decade career of making art and teaching at UC Irvine. The arc of his life has been one of continual inspiration, experimentation and of flow within his individual works and from one to the next. From the late 1950s, almost until the present, he adhered to the principles of Southern California Minimalism — art that is deceptively simple in form and color while eschewing decorative and figurative elements.

He was also associated with other 20th-century movements, including hard-edge painting, which emphasized specific and defined areas of color, and California light and space, which was characterized by its use of industrial materials designed to capture and reflect light. Yet working primarily within the minimalist style, DeLap stretched its boundaries, creating seemingly simple artworks that nevertheless enchanted and mystified viewers through their organic and often meandering three-dimensional shapes. His pieces flawlessly interweaved minimalism, the art of anti-illusion, with magic, the art of illusion.

DeLap’s pioneering method of artmaking was embraced by museums and galleries around the country, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, the Jewish Museum, the Smithsonian Institution, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Mona Lisa (Courtesy of Laguna Art Museum)

While some minimalists rejected the actual process of building their own artworks, DeLap almost always constructed his own canvasses and sculptures. He sawed his own wood, stretched and painted his canvases, and experimented with structures and materials, including metal, fiberglass, molded plastics and fabrics. The results were wall-mounted, low relief, mixed-media constructions that are so distinctive, they almost defy description. The artist also built freestanding aluminum, fiberglass and wooden sculptures.

Supporting and inspiring DeLap’s endeavors was his beloved wife Kathy, who assiduously tracked and catalogued his growing body of work over the years, and lived with him in the same Corona del Mar home near the ocean since 1965. And she helped raise their two creative children, who now have children of their own.

DeLap spent his entire life near the water. He was born in Oakland in 1927 and witnessed the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge (completed in 1937) from the windows of his home. This activity inspired his interest in building model cars and planes as a child and, later, constructing his art. In the 1950s and early ’60s, he worked at various jobs, taking on trade show exhibitions and graphic design gigs while creating his early collages, paintings and sculptures at night.

He became an art professor in San Francisco and then landed a job at UC Davis. In the mid-1960s, he moved to Orange County, where he became part of the original, experimental UC Irvine faculty. The university’s art department back then was a daunting force in the advancement of radical performance and conceptual art. And DeLap participated in the college’s performance art by performing his astonishing magic tricks there. (In fact, he continued to mount his magic tricks, almost until the end of his life, often on stage at L.A.’s The Magic Castle.)

Before opening his large working studio, which was adjacent to his home, DeLap rented a workspace in Costa Mesa, then a thriving shipbuilding hub filled with highly skilled shipwrights. Learning from his neighbors, he honed his construction abilities while evolving as a craftsman as well as an artist.

I asked DeLap why he continued to work in a minimalist mode, years after it ceased to be the de rigueur art movement. He answered that he spent his whole life living on or near water. “When you look at the water, there’s nothing there,” he said. “Water is really serene, metaphysical, Zen-like and poetic.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting Irvine Weekly and our advertisers.