Art can be a powerful political tool; sometimes for good and sometimes for bad. At the best of times, it can lead to social and political evolution, and at the worst of times, it can be used as a scapegoat for fear-based religious and political agendas. A recent theatrical showcase at UCI’s Winifred Smith Hall, on February 22, shined a light on both instances. The show was called Hollywood and the Red Scare: The Deportation of Hanns Eisler, and it provided an audience of around 75 people with a depiction of The House Un-American Activities Committee’s (HUAC) congressional hearing and subsequent deportation of composer Hanns Eisler, in 1948. History has revealed HUAC to be nothing more than a paranoid reaction to the perceived threat of Communist subversion. Thus, while the committee used Eisler’s Hollywood film scores and other orchestral works as “evidence” of Eisler’s alleged acts of subversion, the performance of Eisler’s music — narratively framed using a depiction of this historical chapter, with script by UCI professor Robin Buck (vocal arts/music theater) — employs art to reveal that fascism has and continues to exist, in plain sight, in the U.S. government.

The show was introduced by UCI assistant professor of music history and music theory, Dr. Stephan Hammel, who provided lengthy but informative notes on Eisler’s life, politics, HUAC trial and on the history of the conspiracy that communist ideology was being infused into the works of certain artists and performers. Dr. Hammel revealed, “Eisler was the first musician to appear before a committee that had turned its focus on communist infiltration in Hollywood. … Only a handful of those blacklisted ever made it back into the [entertainment] industry,” and, in reality, “Communist propaganda in the media was no more in danger of sparking proletarian revolution in the United States than the Soviet Union was in a position to sponsor a communist invasion of Colorado across the southern border (the plot of the 1984 film, Red Dawn … a Cold War classic).”

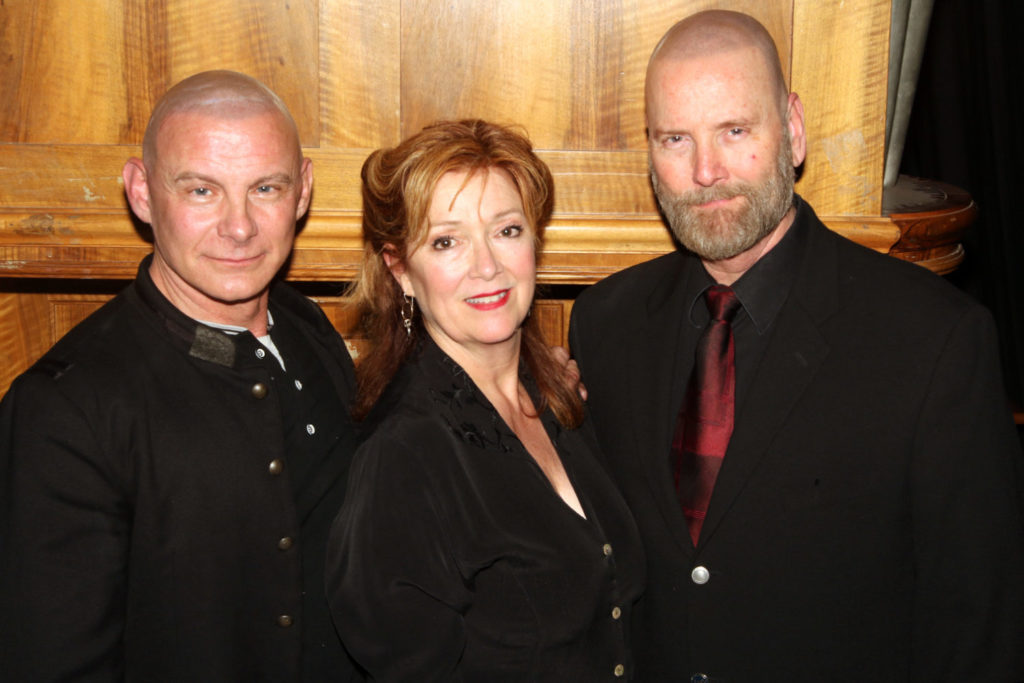

Left to right, Andreas Mitisek, Suzan Hanson, Robin Buck (Scott Feinblatt)

More disturbingly, Hammel illustrated the lineage connecting the Red Scare with the current administration. “The parallels to our own era are hard to avoid drawing,” he said. “The current administration is genealogically descended from McCarthyism, [with] political genes flowing to the White House through the likes of Roy Cohen and Roger Stone. American liberals are convinced that conservatives have breached the norms our governing institutions rely on to function. The charge of indecency is commonplace. The legacy of socialism, indeed of communism, is again on trial.”

Hollywood and the Red Scare was comprised of wonderful musical and spoken word performances by Buck, an acclaimed baritone (Long Beach Opera, NY City Opera, LA Opera, Basel Opera, Zurich Opera, Chicago Symphony, Carnegie Hall, etc.); Suzan Hanson, soprano (LBO, Chicago Opera Theater, San Francisco Opera, Verona, Florence, Carnegie Hall, etc.); and Andreas Mitisek, piano (director/conductor Long Beach Opera, Chicago Opera Theater, Seattle Opera, Arena di Verona, etc.).

The performance began with Hanson, Mitisek and Buck standing at lecterns and re-enacting portions of Eisler’s inquisition, using actual HUAC transcripts to comprise the dialogue. Mitisek was the obvious choice for performing Eisler’s dialogue, as both men were born in Austria. Hanson and Buck performed the roles of congressional inquisitors. Beyond the HUAC re-enactment, the performances of Eisler’s musical selections were further complemented with Eisler’s press quotes and additional dialogue written by Buck. Some of the songs included: “Solidarity Song,” “Spring,” “The Homecoming,” “Hotel Room 1942,” “Nightmare,” and “To be Sung in Prison.”

The show as a whole didn’t so much play like a traditional narrative as it did a work of poetic performance art. The most captivating aspects were the HUAC scenes and the musical performances, which Buck told Irvine Weekly were presented as “evidence” of his insurrection. The songs were performed in German, as originally written, and Buck provided a breakdown. “The first group of songs was focused on when he fled Nazi Germany and the time spent before coming to the U.S; the second group of songs was more specific to his time in Hollywood, ultimately paralleling his rather bitter denunciation of the House Committee, which incidentally included Richard Nixon,” he explained. Regarding the choice to perform them in German, Buck said, “We sang the songs in their original language, and spoke the translations rather than attempt to create singing translations. [Bertolt] Brecht’s texts are phenomenal, and German is such an onomatopoeic language — there’s something quite visceral in singing it.”

Left to right, Robin Buck, Suzan Hanson, Andreas Mitisek (Scott Feinblatt)

This was actually the second performance of Hollywood and the Red Scare. Buck explained the show’s origin. “Last spring, Long Beach Opera asked me to perform songs by Hanns Eisler with Suzan Hanson and Andreas Mitisek as part of a concert presented at the Wende Museum (devoted to the Cold War) in Culver City, in October 2019. Suzan and I were asked to sing the ‘Anthem’ Eisler wrote for the German Democratic Republic in 1949 and choose songs from Eisler’s ‘Hollywood Songbook.’” He continued, “I came up with the idea to contextualize the music, using Eisler’s HUAC testimony and his own words, and began writing a script. In this original version, the music was more interspersed, so probably a bit more impressionistic than linear. It ended with Eisler’s ‘Anthem.’ For the Irvine performance, I chose to finish on a note of condemnation and defiance with his leaving the U.S.”

Buck expects that he will revise and expand upon the show’s structure for future performances to include more about Eisler’s family life; his sister, Ruth Fischer, testified for the HUAC against Eisler and their brother, Gerhardt.

It is refreshing to see that the spirit of revolution persists in theatrical, musical works. For, as Dr. Hammel pointed out, theater can provide the means for great change — and not in the insidious manner suggested by the self-righteous, fear-mongering, congress members of HUAC, but as a reaction to them — as demonstrated by plays like The Crucible, which Hammel referenced in his opening. “Arthur Miller’s staging of American witch hunting would do more to shape the moral meaning of the postwar Red Scare than anything said by politicians at the time or since.” He continued, “The slow, elegant work of this higher kind of propaganda is precisely what the anti-communist suits and haircuts in congress misunderstood about what they were investigating. If a culture war is what they were fighting, they lacked sufficient culture to win.”

Advertising disclosure: We may receive compensation for some of the links in our stories. Thank you for supporting Irvine Weekly and our advertisers.